Dear Readers,

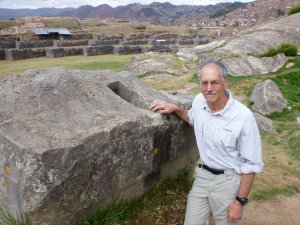

Gregory Deyermenjian has been a Fellow of The Explorers Club, with headquarters in New York city, since 1988, and has organized and led well over a dozen expeditions into the remore areas of mountain, plateau, valley, and jungle to the northeast and north of Cusco, Peru, in seeking clues to the existence, form and location of a lost site known as «Paititi.» He has also participated in expeditions, along with Lewis Scotton of The Explorers Club and with Ecuadorian researcher/explorer Simon Bustamante, in easternmost Ecuador, in tracing a newly identified possible route followed by Francisco de Orellana to the Amazon; and in Roraima in northernmost Brazil, to investigate, along with Chilean researcher Roland Stevenson, the possibility of that the El Dorado legend originated from a real locale there. He has lived all his life (so far!) in the Boston area, where he has worked for many years in the field of Mental Health and Behavioral Services, and in teaching English and Spanish. He has degrees in Anthropology, Special Education, and International Development and Social Change, from the University of Massachusetts, Lesley College, and Clark University, respectively.

Gregory Deyermenjian has been a Fellow of The Explorers Club, with headquarters in New York city, since 1988, and has organized and led well over a dozen expeditions into the remore areas of mountain, plateau, valley, and jungle to the northeast and north of Cusco, Peru, in seeking clues to the existence, form and location of a lost site known as «Paititi.» He has also participated in expeditions, along with Lewis Scotton of The Explorers Club and with Ecuadorian researcher/explorer Simon Bustamante, in easternmost Ecuador, in tracing a newly identified possible route followed by Francisco de Orellana to the Amazon; and in Roraima in northernmost Brazil, to investigate, along with Chilean researcher Roland Stevenson, the possibility of that the El Dorado legend originated from a real locale there. He has lived all his life (so far!) in the Boston area, where he has worked for many years in the field of Mental Health and Behavioral Services, and in teaching English and Spanish. He has degrees in Anthropology, Special Education, and International Development and Social Change, from the University of Massachusetts, Lesley College, and Clark University, respectively.

Part of the quest to answer the question of the existence, form, and location of a lost city known in legend as Paititi, concerns employing a strategy always employed by Hiram Bingham, that of checking out any and all clues that appear, to see for oneself what really may or may be «there,» regardless of how remote the possibility or how difficult the area.

In 1993 my Peruvian expedition partner, Paulino Mamani, and I, realized, upon our reaching the head-water region of the Rio Timpia in the remote Meseta (Plateau) of Pantiacolla, that we would need a helicopter for subsequent expeditions, if we hoped to be able to reach this far-away area with enough time and supplies left to make a thorough exploration. In ’94 and ’95 we still did not have sufficient funds to make that flight to the Pantiacolla, so we went on foot to the jungles of Callanga, documenting its extensive Incan and pre-Incan remains. When 1996 came, we were in the same condition, so we decided to take on the issue of the «Pyramids of Paratoari.» These were huge pyramidal formations that had been spotted on a NASA satellite photograph over 20 years previously, which had generated much wild speculation as to their nature, and their relation to «Paititi.» But, they had yet to be reached, explored, and documented; this is what we would do.

So, in the middle of that year, we–Paulino, Ignacio Mamani; Dante Nunez del Prado; Fernando Neuenschwander; and myself–found ourselves at the Machiguenga Native Community along the Rio Palatoa, where we were joined by a Machiguenga couple, «Roberto» and «Grenci,» with Grenci carrying with her their infant daughter, «Reina.»

Our plan was to ascend the Rio Negro, or «Yana Mayu,» an affluent of the Palatoa. But there was a plethora of rivers, streams, and «quebradas» (ravines) entering the Palatoa from the north; which would be the Yana Mayu? We traced, on our satellite photo map, the course of that river which came from the areas of the pyramidal formations, and wended its way down to its mouth on the Palatoa. We figured the most likely latitude and longitude of that mouth, extrapolating from a known point at one end of the map. And, when we came to those coordinates, there was a dark, miasmic river entering; we would assume that that was the Rio Negro.

We followed this river on its most unpleasant course, as it wound its way around and around, with many deep areas to be crossed, much deep, sucking mud, a sickly and fetid aspect to the water, and through its myriad bothersome insects. Further and further upriver we gradually ascended, until finding ourselves presented with a higher area, that rose precipitously from the left bank of yet another tributary. This must, according to our calculations, we thought, lead to the «pyramids.»

So we began the descent, taking us further and further above, and away from, the river. Up one hillside and down the next. We wondered «Where are the pyramids??» After coming to a large rock face covering the side of one hill, and climbing a particularly high tree atop one to get something of an overview, Paulino announced that we must actually be within the area encompassed by the formations. They we so large, that we had been wandering and searching and camping on them, without realizing it.

The area proved, over the course of the next days, to be among the most difficultly uncomfortable of any yet encountered: intense humidity and heat day and night; very precipitous inclines, making it difficult to find any decent campsite, and forcing us to camp on the narrow, rocky «beach» alongside a local stream, always a dangerous proposition with flash floods always possible; and days filled with sweat-flies lapping our perspiration and bodily fluids, and nights filled with sancudos, mosquitoes and other biting, flying bugs, as well as long lines of ants that would force their way through the tiniest of entrances between the teeth of a tent zipper, necessitating a frantic midnight evacuation and beating of the tent to expel all its invaders.

Our traversing as much of this difficult territory as possible lead us to conclude definitively that the formations were of natural origin: they were not, in reality, of the same size and symmetry, as they appeared in satellite photographs and aerial photos, but were somewhat varied; the exposed rock faces on the pyramidal formations were not of glistening alabaster, as some fanciful writers had suggested, but were in fact of sandstone, easily carved over the years by the effects of rain and wind; although plenty of rock faces in the area, there was not a single petroglyph, artifact, or other sign of ancient occupation to be found; and the extremely «broken» nature of the area, itself, devoid of the agricultural potential or animal life that would be necessary to sustain any native population, seemed to deny the possibility that any hunting, or hunter-gatherer, or swidden-agriculture group would ever be able to sustain itself hereabouts, never mind any culture technologically sophisticated enough to construct or shape large pyramidal formations.

On our last full day in the area, we made an attempt to reach the top of a relatively flat area, that appeared on aerial photos to be platform-like in appearance. The way up the hillside that led to it was particularly difficult and labyrinthine, making necessary Paulino’s many ascents of tall trees in attempts to orientate us, holding out as long as he could while up there against the swarms of particularly virulent buzzing and biting insects. We were forced to turn back to camp before reaching that goal, not wishing to be caught for the night in such an inhospitable area of such an inhospitable region.

Although disappointed in our not reaching «the platform,» I was satisfied with the sufficient thoroughness of what we had done, regarding being able to return with a definitive description of the formations and their very probable natural origin. We named the little creek beside which we had been encamped the «Rio Reina,» in honor of Roberto’s and Grenci’s infant daughter explorer, and followed its southwest course out to a larger river, the Inchipiato, which, by its endless meandering route through a flat changeless landscape, and its expansive rocky beaches covered with enormous cicadas that arose in a mass as we passed through them, buffeting us with their hard shells that made it necessary to cover our exposed faces as best we could against their painful and unpleasant collisions, made us almost long for the Yana Mayu of a couple weeks before.

Finally, we reached the area approaching the major waterway of the Manu region, the grasslands approaching the banks of the Rio Alto Madre de Dios, the «Amaru Mayu» («Wise Serpent River») of Incan times. Here there were scattered cows, and here it was that I acquired a truly debilitating case of chiggers infesting my feet, ankles, and lower legs (that would torment me for the next month until finally getting rid of them by drinking noxious medicinal potions concocted for me in the fledgling Tropical Medicine clinic at my hospital in Boston). We flagged down a passing motorized river canoe, made our way back to the jungle village of Atalaya, and soon completed the land voyage over the high frigid altiplanos to descend to the colonial town of Paucartambo, and thence to where it all had begun, the ancient Incan capital of Cusco.

This had been a detour on the quest to determine the reality behind the Paititi legend within southeast Peru. With Paratoari under our belt, we would now return to a more direct route in following the unmapped Incan «Road of Stone» ever directly northward of Cusco, back to the high, cold remote reaches of the Timpia and the Pantiacolla Plateau…

Link to Website: http://www.paititi.com